Futures are unlike cash instruments such as equities in that they have a limited life span and therefore we lack proper long term data to analyze. We have two main problems to overcome; Which contract to base our time series analysis on and how to link contracts together.

When trading commences for a new contract it is usually quite a long time left to the expiry date and there is very little trading activity to be seen. Few people are interested in trading wheat with a delivery several years from now and as such the contract will remain relatively illiquid until it gets closer to expiry. At any given time, there will be one contract in each market, corn, orange juice, gold etc., which is the most liquid and the contract that almost everyone is trading at the moment. This can sometimes be the contract that is closest to the expiry date, but this is far from certain and there are no firm rules for when the liquidity switches to another contract or even which contract it switches to. For some markets this is very predictable and very straight forward, such as for equity index futures and currency futures, where the most liquid contract with a high degree of certainty is simply the one that has the least time left to expiry and the switch happens on the expiry date itself or just one or two days before it. In some commodity markets both the timing of the switchover and the selection of next active contract is completely unpredictable. For someone focused just on a single market, it is possible to stay close enough to that market to be aware right away when the attention of the traders switch from one contract to another, but as a systematic trader covering a large number of markets you need to find a way to automatically detect such changes. From the perspective of the typical trader, the most liquid contract is the only one that really matters.

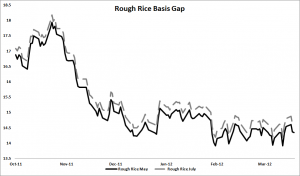

The current price of two contracts with the same underlying but different delivery months will always be different and this is reflected in the term structure. The April gold contract will be traded at a different price than the December gold contract for the same year, and the same logic goes for any other market as well. Usually the price of the December contract will be higher than the April contract of the same year, in which case we have a contango situation, and this has nothing to do with the expectations of gold price changes. It may be intuitive to think that the higher price of the December contract reflects traders’ view that gold spot price should move up, but this is not at all the case. Instead the hedging cost, or carry cost if you will, is the core factor in play. The difference in base price between two contracts becomes acutely important when the currently traded contract comes to end of life and you need to roll to the next.

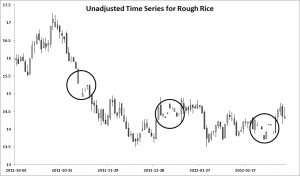

The reason for this price discrepancy is primarily related to hedging or carry costs. The problem that this creates for us is that when creating a continuous time series for long term simulations, one cannot simply put one contract’s price series after another. Doing so would introduce artificial gaps in the data where there really were no gaps in the actual market. What is required to do proper back testing simulations is a continuous time series that reflects the actual market behaviour, which does not necessarily mean that it reflects the actual prices at the time. The chart to the right is a completely unadjusted time series where contract after contract has just been put back to back. The closest contract has always been selected and held until expiry, when the next contract has taken over. This is the default way of looking at continuous futures time series in many market data applications and if you for instance chart the c1 codes in Reuters this is what you get. In this example it is easy to see right away when the contract rollovers occurred, even without the circles that I put in there. The seemingly erratic behaviour of the price during these periods does not at all reflect the actual market conditions at the time and basing your simulations on such data will produce nonsense results.

The reason for this price discrepancy is primarily related to hedging or carry costs. The problem that this creates for us is that when creating a continuous time series for long term simulations, one cannot simply put one contract’s price series after another. Doing so would introduce artificial gaps in the data where there really were no gaps in the actual market. What is required to do proper back testing simulations is a continuous time series that reflects the actual market behaviour, which does not necessarily mean that it reflects the actual prices at the time. The chart to the right is a completely unadjusted time series where contract after contract has just been put back to back. The closest contract has always been selected and held until expiry, when the next contract has taken over. This is the default way of looking at continuous futures time series in many market data applications and if you for instance chart the c1 codes in Reuters this is what you get. In this example it is easy to see right away when the contract rollovers occurred, even without the circles that I put in there. The seemingly erratic behaviour of the price during these periods does not at all reflect the actual market conditions at the time and basing your simulations on such data will produce nonsense results.

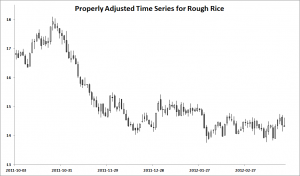

Now compare this with the more normal looking price curve in to the right. Notice how it is no longer possible to see where the contract rollovers occurred and the artificial gaps have been removed. If you look even closer, you will notice that while the final price is in the end the same, there are significant price differences between the two series on the left hand side of the x-axis. While the peak reading in October was about 17.3, the adjusted chart shows a peak of over 18. The difference can occur in either direction, depending on if there is a positive or negative basis gap at the time of the roll. The reason for this price discrepancy in the past prices is that I use back adjusted price charts here. For a back adjusted chart, the current price is always correct at the right hand side of the series, but all previous contracts will have a mismatch. When the roll occurs, the back adjusted series will adjust all series back in time and remove the artificial gap. This means that the whole time series back in time will have to be shifted up or down to match the new series.

Now compare this with the more normal looking price curve in to the right. Notice how it is no longer possible to see where the contract rollovers occurred and the artificial gaps have been removed. If you look even closer, you will notice that while the final price is in the end the same, there are significant price differences between the two series on the left hand side of the x-axis. While the peak reading in October was about 17.3, the adjusted chart shows a peak of over 18. The difference can occur in either direction, depending on if there is a positive or negative basis gap at the time of the roll. The reason for this price discrepancy in the past prices is that I use back adjusted price charts here. For a back adjusted chart, the current price is always correct at the right hand side of the series, but all previous contracts will have a mismatch. When the roll occurs, the back adjusted series will adjust all series back in time and remove the artificial gap. This means that the whole time series back in time will have to be shifted up or down to match the new series.

There are several possible ways to achieve this adjustment and most good market data applications offer a choice in this regard, but it does not make a huge difference for the bigger picture which exact method you go with.

Lucky for you, properly adjusted futures charts suitable for trend analysis are available right here on this website. I have selected the most liquid contracts for each market, rolled with open interest and basis gap adjusted the series so you can analyze the charts right away!

Following the Trend

Following the Trend

Hi Andreas,

I heard that back-adjusted data is the best for backtesting. Nevertheless, which data should we use for live executing of trades? What kind of data do you use for generating signals? Single contracts or back-adjusted ones? Which one would you use for your strategy in your book?

Thanks,

Tom

It’s important to be consistent. You need to simulate the way you will trade, and trade the way that you simulated.

A common way to do this is to use back adjusted data for simulations. The roll method used needs to be the way that you plan to trade later. The advantage here is that the current price point in your simulation will be the same as your real market price. Therefore, you can just continue to run the same simulation every day for signal generation.

I thank you so much! What would we do without you, Andreas?! I can’t wait to buy your next book. Your first book was pleasure to read! 🙂

Tom

Hello Andreas,

Nice article. There is always a battle among practicians on the method to be used to link these futures contract. I would like to know if possible how do you proceed when you are backtesting, in or out of the sample on a continuous price series. Bearing in mind, the continuous price series is by definition modified, in terms of price level, how do you manage to calculate a log return for example or a rate of change? You can’t really based the calculations directly on the continous price series, your results will be wrong. How do you proceed, do you make a nominal change between 2 dates then divide by the nearest futures contract price, as suggested by Schwager. I would really appreciate your comments on how you proceed.

Thank you a lot and all the best.

D

Hi Dave,

It’s a simple topic on the surface but can get quite complex if you dig into it. Your observations are of course completely correct.

What you need to do is to figure out what type of continuation fits best for your purpose. You may want to have multiple versions of each market, to be used for different things.

Log returns for instance work better on a ratio adjusted series than a spliced back adjusted series. For every type of continuation, you’ll find weaknesses. When you start doing more complex things, it’s important to be aware of the weakness of the continuation you use. That helps you understand the end results, what can be trusted and what’s likely just crude approximations.

For instance, log returns on regular back adjusted data is likely good-enough for perhaps a year back, depending on what you’re using it for. The further back you go, you obviously getting a compounding error factor.

So, I guess the tl;dr is ‘it depends’.

Thank you Andreas. Much Appreciated your response and of course your book at large.

Hello Andreas

Thanks for your comments. The topic of futures data adjustment is crucial for testing and trading systems and yet, easily overlooked, in my opinion.

It seems to me that opinions converge on what are the best adjustment methods (among several) to apply to price data for the purpose of testing and trading long-term trend-following systems: 1. backwards additive and 2. backward proportional adjustment.

Any thoughts on which is better, bearing in mind that both can be back-tested and traded the same way (for example, roll on Open Interest trigger, sell old contract/buy new contract on Open).

Thanks

There’s really no better. There’s only different methods that are better suited for different purposes. Of course, if you can you should do proper modelling off actual futures contracts. But that’s near impossible with most consumer grade software solutions. Using something like RightEdge, you can build your own solution for it, which is what we do.

Dear Andreas,

You mention that contango situation has nothing to do with the expectations of gold price changes. Actually the term structure of commodities always show future expectations regardless of whether prices are inverted or contango. It may well be the the December price becomes higher than its carry cost if traders expect that future spot prices will be higher. This is refered to the concept of Risk Premia in futures pricing. It is the theory of futures pricing in addtion to the theory of storage. Please let me know if I am wrong.

Best regards

Okan

While my article here is deliberately simplified, the core premise stands. The curve does not reflect any sort of belief by traders that the spot will go up or down. That’s largely nonsense from academics who never spent a day in the markets, but don’t let that detail stop them from writing papers about it.

Such a concept would be rather comical actually. If a market has had a persistent steep contango for years, then that would imply that traders believed that the spot would move up. Meanwhile, the futures prices keep crashing down since each point on the curve slowly moves down until expiry. It makes no sense, outside of a class room.

A contango pattern is bearish for the futures markets and backwardation is bullish. In the long run of course. But it’s just one factor out of several, and by itself it may not be enough. It’s an important factor that shouldn’t be ignored.

i am actually not only academic but also registered market practicionar since 2000. Curve reflects expectations. From academic standpoint, it is the job of risk premia and convenience yield. From practicionar standpoint it is excess offer of nearby contracts reflecting rush to sell from today since traders “expect” price to fall. That is why contango is bearish. İn case of backwardation traders Rush to buy from today and not postpone with the expectation that prices will rise. That is why backwardation iş bullish. This is the job of convenience yield and risk premia.

Thanks Andreas. I can see how backtesting on actual price data (as opposed to adjusted data) is a natural choice. One question to that point: how do you test the closing of a position in the “old” contract and the opening in the “new” contract? One problem I can think of is of potential incorrect signals generated by entry/exit rules that look back at data (which will contain gaps at rollover dates) with lengthy look-back periods (i.e., 200-day moving average).

Short of testing on actual data (which, as you say, is near impossible with most consumer grade software solutions), is the additive price back-adjustment a good second option for long-term trend-following systems? (assume no percentage or proportion arithmetic involved in the system). In general, based on your experience, what degree of inaccuracy is introduced in backtest results by the inflation/deflation effects of this data-adjustment method?

Thanks again.

Leonardo

Using continuations will always have a certain danger of these kind of errors. Still, it’s the best approximation available to retail. You can use multiple types of continuations for different purposes if you like, to lessen the problem slightly.

If you want to do it more accurately, you’ll have to get all individual contracts and model based on that. It’s not at all impossible. In fact, it’s not even expensive. Just a little tricky… You could do it with RightEdge and free Quandl data, but you’ll have to program it yourself of course.

Hi Andreas,

Firstly, thank you for such a wonderful book.

Could you please let know the importance [or lack thereof] of detrending the futures data within this article? Further, at what duration do you think it becomes relevant.

Also, would be grateful for some guidance on position sizing on synthetics (e.g. Gold/Silver or cracking spreads) as the position sizing on short side becomes smaller compared to the long side.

Many thanks,

Yogesh.

I’ve never seen the point with detrending data.

Careful with synthetic positions, unless you really know what you’re doing and also have a prime broker that nets your margin. You often need to take on very large sizes to get any meaningful impact, which can be very dangerous if you miss some factor. You also need to dynamically rebalance, and that’s another major complication.

Hello Andreas,

In this article and “Don’t analyze the wrong time series” you’ve written about using the importance of using the proper data series when analyzing futures markets.

You’ve indicated on your home page that you’re a user of CSI’s data as am I.

CSI has many methods of constructing a continuous/perpetual futures contract. Which of their methods meets your criteria as a “proper” series on which to conduct analysis?

Thanks,

Robert

Many, and none. Depending on your purpose. 🙂

The easy answer is of course to use back adjusted series, rolled on a few days higher OI, but that’s not always the case. It sure is a whole lot better than using non-adjusted series of course.

What you need to do is to look at how the series will be used, and then apply a bit of common sense. If you’re just looking for the trend, back adjusted futures works fine. If you want to do some correlations studies over longer periods, they will break down fast. Ratio math won’t fair will with back adjusted contracts.

The link to already-adjusted historical futures prices seems to redirect to a different page now (from /futures-charts to /futures-market). Are these charts still available somewhere else? I’ve read the book and was hoping to test the described methods myself.

Hi Kevin,

We moved these charts to the premium section a while back. I’d suggest to either buy the adjusted data from CSI Data (15% discount with coupon code Tradersplace) or if you feel like doing some programming, make a Python script to download all contracts off Quandl and use Pandas to recalc the series.

Hi Andreas,

I have read both your books and they have helped me immensely in both my thought process as well as my trading style. Keep writing…..

I have a couple of questions on the Momentum Strategy:

1) On the Gap calculation, are you measuring the gap from previous close to next day Open, High or Close? Or is it a rapid rise in a short period, say 5 or 10 days?

2) There is a price shock and it is not the week for Portfolio Rebalance yet and the Portfolio has dropped in value by 5% over the Original size (but the Index remains over its 200 day average). Some stocks (falling below 100 day average) have been sold and we need to buy more. Should we be buying using the Original Portfolio size or the revised size? Or wait for the following week to revise the entire Portfolio to the new size and volatility levels?

Thanks again

Thanks for the Quandl suggestion, Andreas. That worked great.

Is the premium section my best bet for seeing futures-specific results for particular trading systems? I’ve attempted to implement the systems described in the book, but would like to double check my results to make sure that I’m doing it correctly. It seems like looking at results for specific types of futures contracts (e.g. corn) would be a better way of debugging than trying to compare the diversified results.

Hi Andreas – I would also very much like to get the results (return and trades) for a couple of specific contracts over a certain period, as Kevin Z has suggested.

Would really help with the debugging.