A random number generator can beat your mutual fund. Given a choice between a random portfolio and a mutual fund, I’ll go with the randomizer every day of the week and twice on Sundays. You think I’m joking? I’m not joking.

Trashing the mutual fund industry is almost like beating a dead horse. Except of course that it’s a thriving, multi billion dollar dead horse. Still, pointing out that all mutual funds fail to do their job is like kicking in open doors. We all know that mutual funds underperform. The SPIVA Scorecards tracks and compares their performance to the respective benchmarks and the results are devastating. On any given 3 year period, around 80-90% of all mutual funds fail to beat their benchmark.

It’s not really the fault of the mutual fund managers. The entire construct of mutual funds prevent them from having a fair chance of matching the benchmark returns. Then again, according to Gordon Gekko, mutual fund managers are sheep, and sheep get slaughtered. Yes, I may have dissed trading quotes in the past, but movie quotes are always applicable.

Ok, so mutual funds are as useless as a… Well, they’re just useless. Leave it at that. But we could get the index return with a passive ETF index tracker. Buying a passive index tracker will give you an overwhelming probability of higher return than buying a mutual fund. If you buy the ETF, you will get the index. There will be a tiny fee, but else you will get exactly the index. But the real question is if you really want the index.

Most indexes are designed as a way to gauge the performance of a market or sector. They were not designed as investment strategies. Yet, that’s how they are used. As investment strategies, indexes are horribly bad and easy to beat.

There are several things wrong with indexes as investment strategies, but the most important point is about position sizing. In index terminology, it’s called weighting. Most modern indexes are market cap weighted, meaning that the higher the total value of a company, the larger the weight. Makes sense, right?

No, not really. What this system means in practice is that Apple has a weight of 3.9% while Diamond Offshore Drilling has a weight of 0.010105%. If both shares make a 3% price move today, AAPL will give a positive index contribution of 0.12%, while DO will contribute with 0.0003%. For DO to contribute with 12 basis points, as AAPL just did, it would have to show a gain of 1,200%. Why do we even bother to pretend that there are 500 stocks in the S&P 500? In reality, we’re just buying a hand full of the world’s largest companies.

Before you say that DO must be a really tiny little company that doesn’t deserve more weight, remember that it’s still a part of the S&P 500 large cap index. It’s a four billion dollar company.

The method of using market cap weighting holds back performance dramatically. If a company is worth four billion dollars, it can still double. Several times. But if a company is worth 750 billion dollars, more than double of the world’s second largest company and more than any other company in the history of companies, how likely is it to double?

Point being, the largest companies are not the ones likely to show the best gains.

I promised you a randomizer that beats the markets, didn’t I? So let’s get back to that.

Here’s our market beating trading system:Well, that just ridiculous, isn’t it? Buying 50 random stocks each month? Sound stupid.

Obviously, running such a strategy once is pointless. Anything can happen. It is after all random. So let’s run it lots of times. Let’s run it 500 times. I made a dummy input variable in the simulation software and used the optimizer to try 500 iterations of this unused variable. Finally a valid use for the optimizer functionality!

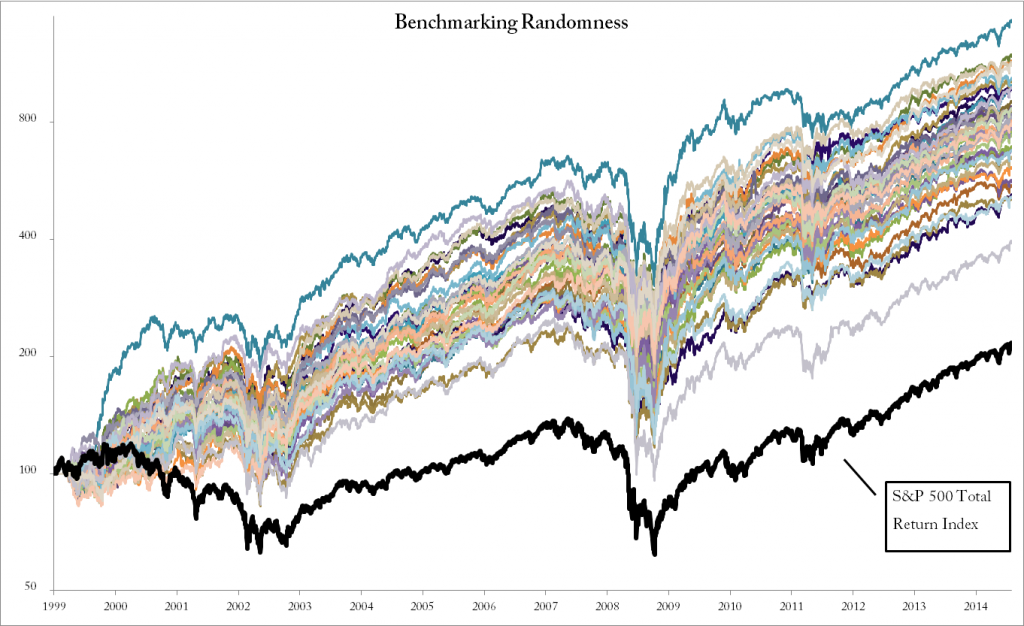

The chart below shows a subset of 50 of these runs. Throwing 500 lines in there wouldn’t add anything. I’ve included both the best run and the worst and made sure that the 50 iterations here are representative to illustrate the results of this exercise.

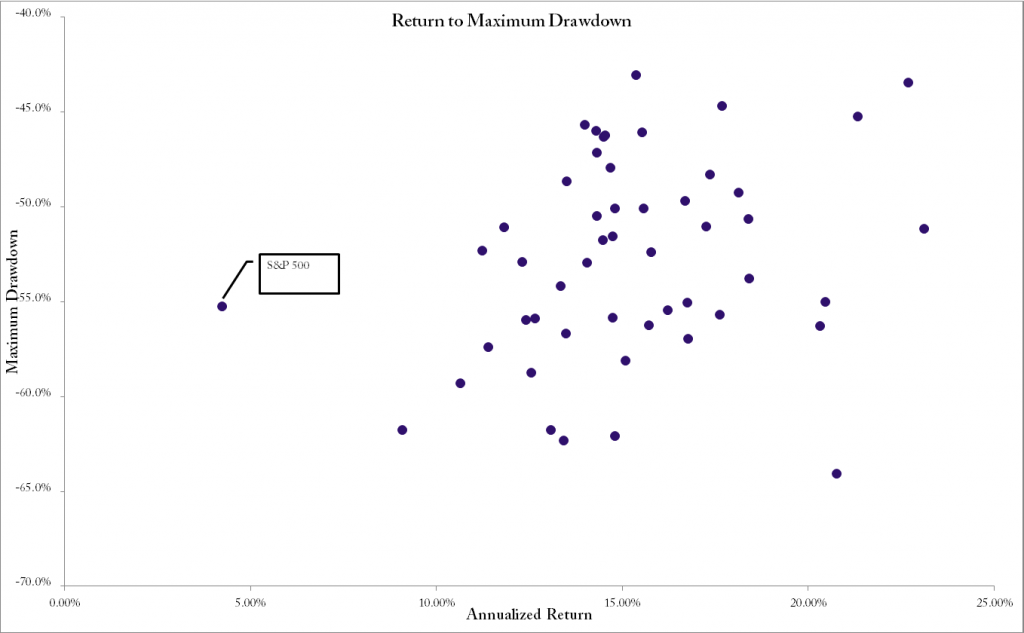

In case you’re curious about those drawdowns and how they relate to the long term annualized return, I’ll throw in another image here below. It shows you a scatter with drawdown and annaulized returns and it should speak loudly all by itself.

Obviously, I’m not actually suggesting that you go and buy 50 random stocks every month. All I want to show is that even such an absurd method has an overwhelming chance of beating the market. What you want to do, is to find a method to ensure that your results are similar to those top performing iterations above. If you can do that, you’ll outperform almost everyone in the world.

Now let me ask you again: Do you really want to invest in the market index?

Following the Trend

Following the Trend

Building on this concept its possible to deomonstrate the benefit of other components of a system, like max loss and trailing stops, whilst still keeping entries random.

What do you mean by “Weight positions by inverse volatility, i.e. simple vola parity sizing”

Do you mean to weight positions more if they are less volatile (like in another article you wrote about leverage: http://www.followingthetrend.com/2014/01/why-leverage-is-pointless/)?

It just means that the more volatile a stock is, the less of it you buy. The effect is that you buy an equal amount of vola in each stock, at least in theory.

Here’s a simple example:

* Settle on what stocks to buy, using whatever method you please.

* Pick a measurement of vola. Most common methods will do. I used ATR for this article.

* Invert the vola for each stock (1/vola).

* Add up the inverted vola for all stocks that you want to own.

* The weight of each stock should now be its inverted vola divided by the total inverted volas.

Or as my five year old son would put it: “Easy piecey, lemon squeezy”.

Lower priced stocks will naturally have smaller ATRs than larger priced stocks. Thus your weighting is heavily dependent on share price not volatility.

*ATRP…

Sorry for the typo, you need to put the ATR in relation to the price first. Yes, it’s still not technically vola, but it’s close enough.

5 year old son? got that little chap trading yet? ;}

My 18 month old already has his own stock account for when he is 18 – Dad’s job is to turn it into something worthwhile in the meantime then show him how I did it!! 16 1/2 year time horizon at an CAGR of…. hmm….

What if we weight the portfolio by the success of the companies? I read that 70% of the stocks in the market ultimately lost money. The performance of indices like S&P 500 are driven by a small number of very successful companies. What if we dump all the losers and recycle them into any random stocks while keep the stocks that are winners?

Sure, we can do that. Weighting by the success of the companies would mean some sort of momentum strategy, right? I only wish someone wrote a good book about that topic…

He could be talking about earnings, i. e. fundamentals, as he talks about “successful companies” and not successful stocks. Not sure about that, though. But the success of the company and that of the stock doesn’t necessarily correlate, right? At least when it comes to present fundamentals and future stock performance.

No I am not talking about fundamentals. Imaging we start a portfolio with N equal weighted stocks picking from a universe say S&P 500 on 1/2000. One month later, l out of the N(l<=N) stocks have a negative return. We sold these stocks and use the remaining money to buy another l stocks. We will never sell a stock as long as it is profitable. We will repeat this process every month. What would happen after a long period of time?

Are you picking your fifty from the constituents of the S&P 500 today, or as it was composed in the past? (ie are you doing a survivorship-bias-free backtest?)

Even if you are, the choice to weight by inverse volatility is hardly random. This portfolio will be heavily skewed towards small-cap stocks and low-volatility stocks, which are two of the biggest risk premia there are (after value and momentum). Not to mention that this strategy would be impossible to implement on more than, say, $500MM.

It’s fine to pick on cap-weighted mutual funds, but then comparing them to a ‘random’ portfolio which can only scale to $100k is not a fair comparison, at all.

Yes, naturally only stocks that were part of the S&P on the day in question were considered. Simulations take historical index constituents into account, as well as delisted stocks, cash dividends etc. Otherwise it wouldn’t be a very good simulation.

I think you’re missing the point a bit with the rest. The weighting isn’t meant to be random. It takes on equal vola per stock, something far more rational than putting the most cash in the largest company.

Implementing this with 500 million wouldn’t be a problem. Not that I’d recommend it, since this is just a demo model, but liquidity isn’t a big problem here. We’re dealing in S&P 500 large cap stocks. The smallest ones in the index are still American large cap stocks.

And as to comparing funds, I didn’t compare the random strategy to the them. I compared mutual funds to ETFs, where the passive ETF wins massively. The random strategy in turn massively beats the passive ETF.

Yes, there are all sort of reasons why mutual funds fail at the only task they’re designed to perform. None of them make mutual funds any more attractive to buy.

Incidentally, I posted this article on Seeking Alpha yesterday. The editors came back to me asking me to revise the title and replace the term ‘ass kicking’ with something more appropriate.

Naturally, my first instinct was to replace it with ‘ass whopping’.

Having evaluated the probability of a Seeking Alpha editor with a sense of humor, I promptly change the title to ‘A random beat down of Wall Street’. The nice part about writing on my own site is that no one can redact my terrible sense of humor…

Andreas,

I tried to reproduce your backtest using top 3000 of the most liquid US stocks (and also using the whole US stock universe) and it doesn’t seem to work anywhere. (CAGR ~ 6.5% for “random 50” approach vs. CAGR of ~ 11% for the whole universe cap-weighted). In other words, it underperforms greatly.

I doubt it works on S&P 500 as well. So, once again, are you sure your backtest is survivorship bias-free?

Yes.

Another thought provoking article! I have been doing similar work using random entries. Just curious if you included transaction costs or any slippage in these results? Thanks.

Thanks, Joe. The model uses realistic entries but no commissions. Your commissions are likely very different from mine and that would need to be added in to make it realistic, if you could use the word realistic about a silly demo model with random stock portfolios of course… No one in their right mind will trade such a model, but there are still lessons to be learned by it.

“All I want to show is that even such an absurd method has an overwhelming chance of beating the market. What you want to do, is to find a method to ensure that your results are similar to those top performing iterations above. If you can do that, you’ll outperform almost everyone in the world.”

Your statement does not make any sense. This is not a method but a simulation. You can’t trade a simulation. You can’t find a method to get top results. You are talking non-sense here. There is not deterministic method to beat a stochastic process. Either you are a joker or you have no knowledge of stochastic processes. Do you understand this? I mean that you cannot determine the outcome of a stochastic process from initial conditions only?

Hi Bob. Thanks for playing.

You completely misunderstood a couple of sentences and decided that the best course of action would be to write a rude and patronizing comment to show how smart you presumably are instead of trying to figure out what was intended. Good for you.

Had you asked nicer, I would have explained.

Have a nice weekend!

Hi Andreas

Entertaining article. Picking just 10% of the available stocks I would expect the average volatility of your random strategy to be higher than that of the index despite your attemts to dampen it and and that is probably the main reason for the out performance. This would imply higher maximum Dradowns than the index which the chart does seem to indicate but hard to be certain. Would be interesting to see those stats as well as a control based on some other weighting system.

Hi andreas,

I like your point when it comes to using a) volatility position sizing as opposed to b) market cap weighting which obviously outperforms the latter. To challenge the validity of your simulation, did you try using the same simulation (using 50 random stocks) but using market cap weighting? This serves as a control and I’m expecting that the equities would form around the index. This validates the claim that it’s really volatility position sizing which caused the outperformance and not some unknown variable.

I didn’t run this sim using market cap weighting. The problem is that then we’re taking the whole random thing to a very different level. If for instance Apple would be included as one of the 50 stocks in one run, that portfolio would look as if you just bought Apple. With 50 random stocks at market cap weight, you would see some diversified portfolios and some where only one stock matters. The weighting percentages would have extreme swings.

More relevant in my view would be to do equal cash weighting. That, as silly as it is in concept, still shows significant outperformance on the index.

Hi Andreas,

I don’t really agree using market cap weighting and yes, I agree with you that position sizing using volatility or equal cash weighting is better. But the way I look at the graph, I’m not thoroughly convinced that the random stocks outperformed the index. For years 2002 onwards, the slope/shape of the equity curves and the index were the same. It’s only in the starting point from 1999 to 2002 which caused the difference (index was lower). It’s possible that the random equity curves at this times were better because they were holding mostly cash since it’s only starting to build its portfolio. On the other hand, the index was already affected by market movement and bad luck, market had a steep decline in 2000. (or probably an unknown variable which caused the difference) My theory is that, had you started that simulation at a year where index was increasing (say 2002), index would outperform the random equity curves (or at least at par, but not underperform).

Hi again,

I just realized. Maybe some large-cap company had something to do with the decline due to the market cap weighting method (and will likely to persist in the future). With this, I rest my case. =) Thanks again Andreas.

Actually this simulation ass-whips all the stock valuation models as well. People spend so much time in finding just the right metric to evaluate the ‘intrinsic value’ of a stock, and very few of them aare able to beat the indexes.

I’m 100% invested in stocks. I have 15 equal weight positions (in $) in my portfolio. How can I calculate optimal volatilitybased positionsize like you suggest in this article?

Try this and see how much difference it would make. Depending on how similar your 15 stocks are, it might make a large difference or a very small one.

* Calculate any vola approximation for each stock. ATRP is a simple and easy to use method.

* Invert it.

* Add all inversted ATRP up, for all portfolio stocks.

* For each stock, divide its inverted ATRP by the sum of all inverted ATRP for the 15 stocks.

* That ratio is your target portfolio weight.

Hi Andreas,

Became a big fan after reading ur 1st book. Reading this article after ur 12 month ROC article has lead to my beliefs systems being challenged. i trade based on my systems. grt job. kudos.

Thanks, Doc!

The Think or Swim platform on TD Ameritrade brokerage will calculate the VIX for any individual stock. Would that be a better volatility metric to use?

Andreas, I’ve followed your blog for a long time and have both your books (finishing the 2nd one now). Kudos to you for providing such great information for retail traders. I’ll post an Amazon review of your second book after I’ve finished.

On this topic of randomly chosen portfolios beating the cap weighted index, there was a great article in the summer 2013 Journal of Portfolio Management: http://bit.ly/1bcOAh3

Basically they show that a bunch of different portfolio weighting schemes, including random, unanimously outperform the cap weighted index. They also test the portfolios using the Fama-French 4 factor model and find that the out-performance of all of the portfolios can be explained primarily by the value and small-size anomalies.

Absolutely right, Dave.

I just wrote an article for a trading magazine in the US on that exact topic. I did random stock selection and random position sizing. Still has an overwhelming chance at beating the index. Add a trend filter and you’re practically guaranteed to beat it.

The important part to me is that once you realize that random everything beats the index, that should change the direction of your research. It’s about the big factors, not the details. Get rid of cap weighting and you’ve taken a huge step forward. Find a rational way to select stocks, be it value, growth or other factors, and you’ve taken another big step forward. Figure out when not to be long, and you’re close to a complete strategy already.

The problem is that it seems so much more fun to fiddle with technical indicators, fibonacci ratios and such things, so that’s where the retail community tends to focus, completely missing the plot.

Thanks for the reply Andreas. Would you mind sharing which magazine you wrote the article for so I can read it?

Yep, I’m in the same mindset as you. Focus on the big factors that have stood the test of time and research and are most likely to continue. But of course there is a lot of money to be made by selling to the desire to find some magic formula that if you can just find it, will guarantee large returns and make you rich!

I’m glad you tell the real story.

It’s a new magazine called Modern Trader. My understanding is that this is the old Futures Mag that’s reborn and rebranded. Still run by Dan Collins. I don’t yet know when it will be published, but it’s common with a lead time of around three months.

Andreas – great to hear you’ll be contributing to Modern Trader!

it’s quite a different feel from Futures mag, but I’m sure it will grow on me.

Andreas

Just found your website today, and I truly like it. My personal market experience of over 15 years, brought me to very very similar conclusions as the ones you wrote.

Curious, though you’re not intending to trade the above system – how did it perform on shorter time frames? (i.e Picking 1999 as a starting year isn’t exactly a naive selection, but probably an extreme selection to make your point more obvious, right?)

Selecting 1999 as starting point was semi-random, if that’s even a word. At first, I wanted to do 15 years. Then I quickly realized that 15 years would mean that the simulation would start off in bear mode, which wouldn’t make a fair comparison and would potentially be quite confusing to readers. The strategy would start off holding zero stocks while the market kept falling. It would make the strategy look great, but it would also look weird.

So I figured, why not include the 1990/2000 market turnaround to show how that was handled too. Seemed more fair to me.

I could have included the 90s, but that would again not seem very fair. It was an amazing bull market, and of course equity momentum would do great. If anything, including the 70s would make it more interested, though then we run into the problem of how reliable any simulation is for such long time periods.

On shorter time frames, anything can happen. Any given year, we might underperform or outperform. We might lose money or we might gain it. It’s a long term strategy that can deviate heavily from the bench. Example from recent real life trading it:

– It underperformed significantly late last year, as the trend filter dipped into red, and then came back up. That means that we scaled out, took losses, and had to get back in on higher prices.

– Then we ourperformed strongly as energies were tanking. The strategy didn’t hold energy stocks, so it had large relative gains.

– In the wobbly market the past couple of months, the strategy has been showing slight underperformance. It’s been quite boring actually, and not much big happening in the portfolio.

As usual, if you look at a long term track record, it looks like a lot of action, but when you’re in it, most of the time it’s slow and uneventful.

you’re a “down to the bottom” person, Andreas. Much appreciated, keep up the good work.

MK

Good article once again, never though about the indices and weighting like that, actually never paid attention on weighting at all as I’m still newbie on investing. Need to start looking indices differently now on. Surely you could find differently weighted indices?

Volatility for weighting?

Jack Schwager says that big mistake that investors make is to define risk as synonymous with volatility, low volatility is not necessarily always reflection of low risk. Low volatility looks good until there is an earthquake kinda event. For example selling swiss franc options looked low risk until the shock hit the market. Historically low volatility looks low risk until the earthquake hits the market. Schwager explains this better than I do, so here is a clip about the volatility from the 2:58 min mark https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ye69i4e5IlM He talks about this almost every interview I have seen from him.

I would like to hear your thoughts about the volatility as a risk measurement and just wondering is it good idea to use volatility for weighting for the reasons mentioned above or is it the best risk measurement we have? What about equal weighting or any other measurements to use for weighting?

It’s all down to semantics really.

Risk is about volatility. But of course, that doesn’t mean that you can make unrealistic assumptions about volatility and expect them to hold up.

The CHF example is perfect. Actually, even better is the EURCHF. A one sided peg, leading to a near zero vola cross. Making an assumption that historical vola is good guide going forward is frankly stupid. I know that a lot of funds got caught with their pants down on that one, but I still say it’s stupid. No one expected it to break the way it did, but it was clear that it could only break big in one direction.

Being long rates on near zero yield levels is similar. Sudden large moves could only happen in one direction. The risk is clearly asymmetric. Assessing risk isn’t only about looking at past volatility, but that’s a good start.

The way that I explain risk in my books and on this site is highly simplified. It’s meant to teach people who don’t really know much about risk to begin with. If you’re already got an FRM and are working with stress testing and complex VaR models in the mid office in a large bank, well then you don’t need my simplistic advise.

The problem is that in the retail space, most people don’t understand at all what risk is. Trading book authors with no financial education and no experience in the field tend to make up their own definitions, and retail traders think that this is reality. A good example is defining risk as “How much money I lose if all my positions drop down to their stop loss points”, which really doesn’t say anything about your actual risk.

Jack of course knows what he’s talking about. He’s a good FoF manager with many years in the field.

Hello Andreas

What if you use the Option Vega to determined the volatility, than your impilicit volatility is your risk (except if a earthquake happens or a terrorist attack)

In your post on September 7, 2015 at 08:32. You mension the RF (EURCHF) risk (big postion because the volatility was low) and i asume that option traders are aware of possible future volatility.

Because option trader always include the implicit volatility which is higher than the real volatility.

regards rick

You might be making things overly complicated there. Make sure you get sufficient added value when you add complexity.

Andreas by ATRP do you mean ATR percentage. That is ATR/PRICE * 100?

Yes, ATR%.

“Then I quickly realized that 15 years would mean that the simulation would start off in bear mode, which wouldn’t make a fair comparison and would potentially be quite confusing to readers. The strategy would start off holding zero stocks”

at the top it says “always be fully invested”.

does the simulation have a slow/fast EMA thing so it is only long at certain times? or is it really always fully invested?

really interesting article!

Always be fully invested refers to the strategy explained in this article. The zero stock comment refers to the strategy explained in the book. Sorry for the confusion.